CONTEXT. OPTIMISTIC SCENARIO

The problems facing the world after the COVID-19 pandemic will have two key aspects: medical and political-economic. In the case of the first issue, everything is more or less comprehensible. No mass vaccination, and no mass use of truly effective medicines is anticipated in the near future (if respective medicines are developed, their widespread application will be blocked by a number of specialists and organisations, and also simply ambitious sceptics interested in slowing down any specific project). That is why all the commotion over the pandemic will continue until society is overwhelmed by psychological exhaustion or until an effective and affordable vaccine becomes available. Subsequently COVID-19 will simply takes its place among a number of unpleasant, but at the same time not necessarily fatal diseases. People are used to everything, inter alia, to far more menacing and dangerous things. Our lifestyles, habits, consumption – it goes without saying that everything is changing, but slowly, and more often for other reasons.

The economic aspect is also more or less predictable. It is already clear today – provided there is no new horrific turn of events, that the consequences of recent months will be unpleasant, but not catastrophic. The markets will not collapse, production globally will not come to a halt, an all-out war (even trade wars) will not happen. There are no signs that the global hierarchy will change materially: all the global players will remain in their places, in any case for the foreseeable future, regardless of who tries to inject so much money into the economies of individual Western countries (individuals and corporates will take everything that they are given, and given that the amounts of the injections are virtually equal in all leading countries – 10-20% of GDP – the level and quality of business activity on emergence from the epidemic will also be virtually identical).

It goes without saying that something will change. It is highly likely that the topic of globalisation for the time being will appear to have run its course. Hardly anyone will want to agree to the delegation of powers to international institutes and organisations, and it is highly likely that existing bodies will be cut down in some way or other. All further regional economic and political integration projects will de facto be frozen, even though international bureaucracy as in the past will produce reams of reports and decisions (or to be more accurate, megabytes) and create the illusion of progress.

National bureaucracies will focus more and more on “safety”. This complies, first and foremost with class interests (each social group always seeks to intensify its powers and influence), and secondly — individual consciousness (fear of the unknown is an intrinsic trait of humanity, even if we refuse to acknowledge this fact). There will be major restrictions, in particular on cross-border activities. So-called “value chains” will become perceptibly more local (this is already being observed in a number of countries). Any forms of foreign presence and investments will be perceived with greater vigilance and even hostility.

One can expect an increase in nationalist moods — in the best-case scenario – isolationist, but also aggressive, unfortunately, as well. Such developments are particularly likely in countries where powerful authoritative rulers will be able to dictate the public agenda. Incidentally, this is almost inevitable in today’s Russia: nationalism pandering to Stalinism is already becoming part of state policy.

Competitive political systems (democracies) will also feel these shifts: control over the electoral agenda has already been relaxed there, predetermining the rise of populism, while it is always far harder to restore/intensify controls than to relax them. It is easy to pander to the moods of the masses, but hard to discipline them.

The trade and economic confrontation between the USA and China alone, coupled with the growing ambitions of China’s leadership – both from a national and regional perspective (the new onslaught on Hong Kong’s autonomy, its increasing aggression towards Taiwan, reflected, in particular, in the discussion about Taiwan’s membership of WHO), and also from the perspective of its global leadership aspirations — will be sufficient to maintain permanent tension globally.

There will be more conflicts, while efforts to resolve them will become less and less productive. One can forget about disarmament for a long time. Possibly, for a considerable period of time.

In the best-case scenario, we will find ourselves in this situation or thereabout by the end of the year.

THE ECONOMY. REALISTIC SCENARIO

According to the competent estimates of European specialists, as a result of the epidemic and responses to it, approximately 10% of the economy that existed previously has already disappeared in Western countries, and for a very protracted period. Demand for the products of this market share will not recover in the required amount for several years. Neither people nor organisations will be able to remain idle for so long, while at the same time retaining the necessary competencies and desire to apply them. Organisations will be reformatted, while people will find new professions or will as a rule withdraw from economic activity.

This applies to Russia to the same degree, or even more. When we talk about 10% of the economy based on the number of employed, we are talking about a significant number of people. And we are not talking here about expenses on benefits or payment for retraining. The problem is that when so many people in the country experience such significant stress in their lives, all the more so against the backdrop of a real threat of loss of health, society as a whole starts to become frantic.

At the same time, there will be serious changes to the part of the economy which survives in some form, and employees will not benefit from these changes. Based on the example of enterprises coming out of lockdown in China’s Wuhan, it is clear that wherever this is not associated with a prohibitively high level of costs, “live” labour will be replaced by technology, as it turns out to be more reliable and more efficient in the long term. Meanwhile heightened requirements will be imposed on all other employees – both regarding their physical health and also their professional competencies, including the ability to combine functions. And this is all will proceed against the backdrop of the victory march of digitisation, which posed the risk, even without any Coronavirus, of triggering an unprecedented reduction in requirements for accountants, planners and other economists, and also the employees of departments related to paper-based document management. Tough times lie ahead not only for the industrial proletariat eulogised by Marx, who did not end up victorious globally, but also for the proverbial office drones.

In addition, further expansion of the personal services sector ended up suspended in animation. Until recently, such expansion had appeared to many people to offer salvation and a solution to numerous problems related to the objective decline in requirements for a new workforce in traditional sectors. If the heightened requirements on health and safety remain for a long time (if not forever, which might well be the case), then this will have a perceptible impact on demand dynamics for personal services, and in general on the development of this sector. For the current campaign to tackle the infection will also have psychological consequences which will outlive the actual epidemic for a long time. In this situation if there are positive shifts in the service economy, then it is highly likely that they will be related to opportunities to offer the mass consumer various services remotely with the use of the minimum possible workforce. Consequently, the problem of unemployment will become extremely acute.

Finally, the problem of structural inconsistencies on the labour market has to be raised. An inability to provide the necessary conditions for full-time studies, the rapid forced transition to the mass use of remote forms of studies in the short term and possibly medium term will undermine the compliance between requirements impose on the competencies of new employees and their supply. And the significant imbalances on the labour market could intensify even more.

In Russia all these adverse economic phenomena, all this disorder, will be superimposed on the fundamental inefficiencies of the actual model of the Russian economy, on the fall in oil and gas prices, and sanctions. Global markets are also experiencing tough times: they had not still managed to overcome the causes and result of the 2008 crisis (see Financial Crisis: Coming Round Full Circle, January 2019), when the pandemic appeared with its unprecedented economic consequences (see How the Economy Will Look After the Coronavirus Pandemic, April 2020).

As a result, it transpires that both hopes and rational calculations will push more and more people to turn to the state: some will line up for help, others for employment, preferably jobs for life, while others will raise grievances that they are not only missing out in everyday life, but are also being dealt a short hand when it comes to justice, as people understand it in the current conditions.

All this will happen soon in Russia – this is 100 per cent likely. And it will no longer be possible to disregard such developments, to pretend that the state in the country only exists for ideas, constitutional concepts and legends about our great past — if for no other reason that the lack of consistent actions implemented by the authorities also represents a response, and is extremely telling. And even if this is not followed by protests or overt mass indignation, elementary conclusions will all the same time be drawn and the non-participation of citizens in any government initiatives will be virtually guaranteed.

This is because it is only in a calm, stable and what is equally important, halcyon time that the inertia of public consciousness may be replaced by the responsible and effective policy of the authorities. At times of crises and abrupt changes, inertia cuts no ice: public trust in the authorities is required, albeit even in a passive form. For trust in money, banks, the actions of the police on local administration is based specifically on trust in the authorities. Finally, well organised daily lives are structured on this basis. And without such a structure, what kind of economy can we even talk about?

For the time being the situation from this perspective does not provide any grounds for optimism. It would appear that the Russian government is providing some kind of material assistance, but in very limited scales, even shamefully so (less than 3% of GDP). However, there are no plans to expand employment or at the very least maintain levels in the private sector. For the time being, this only concerns the development of a strategy for the phased lifting of restrictions on the activity of enterprises covered by them. Taking account of the dynamics of the epidemiological situation and the potential of the Russian bureaucratic system, the actual restoration of the conditions for fully-fledged activity in Russia will drag on for long months, while workplace losses will be widespread and long-term.

It is clear that special state efforts are required to extricate the country from this crisis and revive the economy. This also concerns healthcare and education, and many other sectors of life. The success of these efforts will be contingent first and foremost on the state decisions being adopted, in other words, on the quality of the actual regime and its policies. Will the modern Russian state be able and ready to help the Russian economy recover after lockdown? And to what extent?

SETTING ITSELF A DIFFERENT GOAL

Today hardly anyone in Russia can talk about future trends with any degree of confidence. People have no idea about the thoughts and plans of the country’s leadership – they assess the state’s intentions from what they hear and see on federal TV channels and their online versions

And they see how in an interview recorded last autumn and tossed out to the mass media in May 2020 President Putin calls Russia a “separate civilisation”, and for good measure talks about a weapon that “no other country in the world has”. This is being done against the backdrop of the collapse of key international arms control agreements, Russia’s pointless participation in civil wars in Syria and Libya, the build-up of confrontation with virtually the entire outside world: with Europe, the USA, its nearest neighbours – Ukraine, Georgia and even Belarus. Owing to such policies during the 20 years of Putin’s rule, Russia has not simply failed to become part of modern civilisation, but has on the contrary ended up as a “fracture caught between civilisations” (see The Path That Wasn’t There, 2015).

In addition, such statements by the Head of State constitute an unambiguous political declaration requiring budget expenditure running into countless billions. And on this basis the authorities state that no decline in oil prices and economic and social crisis caused by the pandemic should prevent expenses on geopolitical adventures and confrontation.

Over the past few months under cover of the pandemic an authoritarian corporate regime is being created in Russia with an irremovable regime: anti-constitutional adjustments to the Constitution are about to be adopted, electronic and postal voting is being introduced (which will guarantee full political control and thereby liquidate once and for all the institute of elections) and digital control over the population, the army is being transformed into a closed organisation (President Putin has already compelled Russian soldiers to conceal their affiliation to the army).

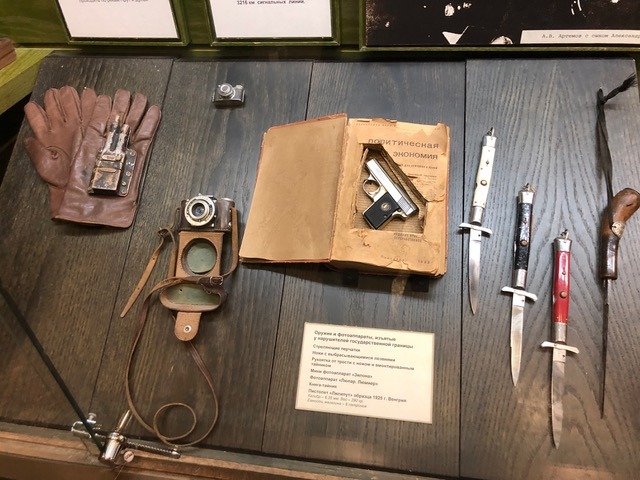

According to this concept and based on the firm conviction of the country’s senior leadership, Russia does not have the slightest chance to end this war, because this is the historical intent and sole meaning of the Russian state. And all of Russia’s citizens are footmen in this war for the glorious past of the country, while the economy is merely a way to mobilise the resources required to conduct this war. The reserves accumulated in previous years are intended specifically for this war: for critical imports, emergency import substitution, army supplies, sabotage and the fight against hostile operatives, the intelligence services and propaganda, in other words, everything that you need to fight both external and internal enemies, and not a recession or a fall in people’s earnings. In this system the choice left to business is meagre: either adapt to the proposed course, and learn how to make money in the process, or quit the game, preferably without the expropriation of your assets, but if this doesn’t happen, then including such expropriation.

To all intents and appearances, whoever determines policy in the Kremlin (and at the same time prepares methodologies for the presenters of talk shows on state TV channels), believes that saving the economy in its previous form is irrelevant and unnecessary.

In actual fact, if one proceeds from the premise that the main mission of Russia is to combat the collective West, “conquer adjacent land areas”, and positions throughout the world, and prepare for a fight to the death with the perennial “historical enemy”, then the country needs a different type of economy: all the resources should be mobilised for these objectives. And the reserves as well.

The reserves will be very helpful, for example, when the West cuts the country off from foreign markets, loans, sophisticated technologies for the production of raw materials, the components required to make weapons and vital equipment. In addition, continuation of the hybrid war with the West will require the full and utter repudiation of procurements of computer equipment and software from the West, and additional funds will be spent on revamping it accordingly, something that has already been declared as a top priority.

Small and medium-sized businesses in the consumer segment is perceived by the Kremlin as a weed: in other words, its grows independently without any policy, and if it is hacked down by the crisis, a new weed will take its place. It goes without saying that this sector delivers a benefit: it helps supply the population with food, employs a significant number of people who would otherwise hang around doing nothing and create problems. However, the regime is convinced that wasting (“burning”) resources on the special cultivation of the “weed” – would be overkill.

Such perceptions of Russia’s mission and priorities are expressed not only by the Kremlin elite, but also by the entire establishment of Russian society, including its intellectually advanced proponents. These views are shared, in particular, by most representatives of the research and technical intelligentsia, a significant proportion of the cultural elite, the teaching staff of institutes of higher education, a number of representatives of the business community, and first and foremost quasi-state big business – even though it is finding it extremely hard to develop relations with the elite from the security and law enforcement forces. Moreover, the owners of small and medium-sized business, even though they are offended by the lack of support from the authorities, share in general the imperial and anti-Western sentiment.

There are a number of reasons why such views are prevalent among the Russian elite. However, what is important here is the result, and not the underlying causes: the fact that the idea of opposing the West provides the authorities with a high level of support from the top strata of Russian society, and determines the main areas of internal policy for the short term – first and foremost, further centralisation of the resources in the hands of the unitary state, the supremacy of the idea of one single, undivided regime (without any checks and counterbalances and any real separation of powers), the prevalence of foreign policy objectives over economic objectives. In other words, to all intents and purposes, this represents the set of ideas of an authoritarian corporate state.

However, the existence of such ideas is not the problem – the problem is that today they are prevailing amongst the Russian ruling elite. Such ideas may not lead to consensus, but do underpin a system of representations on the state authorities which are acceptable to all key segments of leadership. Today they all accept authoritarianism and confrontational relations with the West as an objective reality with no functional alternatives in the here and now.

The hopes for generational change may also not be justified and may even exacerbate the problem. The new generation is growing up in an atmosphere of war and confrontation. For modern Russian youth the developing shifts in consciousness and conversations on the possibility of a nuclear conflict with calculations of the resources and losses – this is the “new normal”.

In the anti-Western authoritarian mainstream in Russia the camps differ significantly. The representatives of one camp are inclined to adopt a wait-and-see approach – they hold a conciliatory stance on unprincipled issues and are gradually preparing for a possible deterioration in the situation through the accumulation of force and reserves. By contrast, other companies are promoting proactive approaches towards the entire external perimeter (above all, in respect of Ukraine), with a clean-up of the “rear” and preparations for a fight to the death already in the near future. They focus on the assertion that today the West “is rotten to the core” and cannot offer serious resistance (as the President of one of the Russian nuclear centres said, it is a giant “with feet of clay”, which will allegedly not be able to withstand serious confrontation), and propose assaulting its position in the most important areas. Unfortunately, Russia’s immediate future will to a large extent be determined by the correlation of forces and the activity of these two anti-Western camps. The second camp may leverage the current and future difficulties of the countries of the Western world, to promote more decisive actions. At present only one thing is holding back the representatives of this camp – the lack of charismatic leaders.

Even if the aforementioned approach does not fully reflect the plans and views of the pinnacle of the Russian regime, this will already be irrelevant after a certain point in time. So if the vast state ship is definitively gaining momentum, it will no longer be able to change its trajectory during this brief short historical timeframe, regardless of what the people in the captain’s bridge might think.

So the Russian economy is entering a serious crisis. The crisis will be particularly devastating for Russia owing to the decrepit state of the economic model, many years of inefficiency, falling oil and gas prices and sanctions. The state might, by making a serious effort, be able to extricate the economy from a post-lockdown torpor. However, Russia’s regime is of poor quality and accordingly it does not have any smart policies. Putin’s regime will not invest the amount in the economy that is objectively required, as it considers the fight with the West to be its historical mission, and not the creation of a modern economy and an increase in the prosperity of its citizens. This is the crux of the Russian crisis and not COVID-19. The focus of the Russian establishment on the fight with the West is becoming dangerous for Russia and the world.