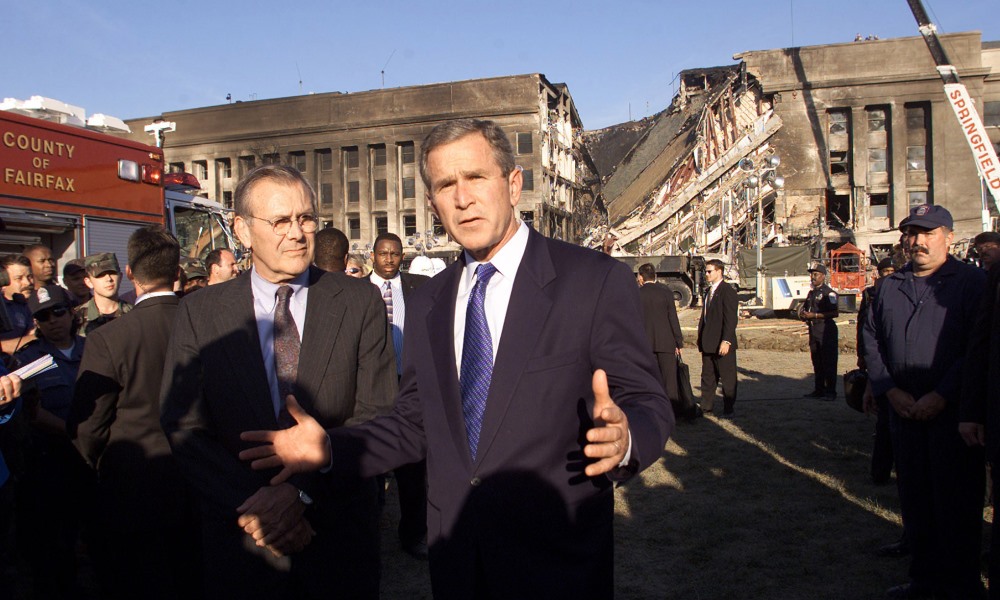

The terrorist attack on the USA on 11 September 2001 signalled the onset of an era of qualitatively new challenges and demands on international politics. Meanwhile that period 20 years ago was an auspicious moment for addressing these challenges consciously and together. Russia was a member of the G8: in February 2001 the Secretary General of NATO George Robertson paid a visit to Moscow during which Russia’s President Vladimir Putin proposed that he contemplate the possible creation by Russia, the EU and the USA of a joint anti-missile defence system for Europe1Vladimir Putin Holds Negotiations with the Secretary General of NATO George Robertson // Official website of the President of Russia, 20 February 2001. Available at (accessed on 11 September 2021).. In addition, Putin was one of the first leaders in the world to declare his support for the decision by the administration of US President George W. Bush to fight terrorism. The Russian President expressed such support, going against the opinion of most of the representatives of Russia’s political “elite”: almost everyone present at Putin’s meeting in September 2001 with the leaders of the State Duma factions and the Presidium of the State Council advocated that Russian preserve its special position — neutrality in the battle against terrorists (moreover one of the attendees even proposed supporting Al-Qaeda). And at this meeting only two participants — Boris Nemtsov, as leader of the Union of Right Forces (abbreviated in Russian as SPS) , and I myself as leader of Yabloko — declared that it was in Russia’s interests at this important time to express our solidarity with America. Putin’s decision might have been attributable to a desire in the context of the Chechen war to stress that the fight against terrorism was a common objective and that Russia should not be constantly reproached over its counter-terrorist operations in the North Caucasus. Nevertheless, this time represented a favourable opportunity for cooperation not only between Russia and the USA, but also for the world as a whole. There was also the sensation that as we represented a common civilisation, we could stand shoulder to shoulder on the most important global development issues and counteract the threats of a new level2 I presented the strategic potential and mutual benefits of Russian-American cooperation in the article published in May 2002. See G. Yavlinsky. The Door to Europe Can be Found in Washington // Official website of Grigory Yavlinsky,16 May 2002. Available at (accessed on 11 September 2021)..

“MOSQUITO HUNT”

In early February 2002 I met up in Washington with Condoleezza Rice, who was at the time the national security adviser of the US President, and some of her employees. We discussed preparations for an agreement on new strategic relations between the Russian Federation and the United States of America, which was to be signed during the planned visit of the US President to Moscow3 See the Moscow Declaration on New Strategic Relations between the Russian Federation and the United States of America // Official website of the Russian President, 24 May 2002. Available at (accessed on 30 August 2021).. The conversation turned to US military operations in Afghanistan and the planned invasion of Iraq. Assessing US actions, I noted that America naturally ranked number one globally in terms of the level of armaments and army capabilities, as well as economic potential and scale of influence on international politics. Although in reality America occupied all the rankings from first to tenth in this area. However, this only concerned 20th century standards. I noted: “In the 21st century, everything is already different.” Silence ensued in the office in Washington. Several seconds later Ms Rice asked me to explain what I meant.

And I explained to the best of my ability. I said: “Imagine that you intend to go and hunt big and dangerous animals. To do so, naturally you will take the respective weapon with you: powerful full-bore rifles, sports rifles, carbines, etc. And so you enter the jungle — and are suddenly attacked by deadly poisonous mosquitoes. What can you do with your wonderful weapon? How will your hypothetical aircraft carriers, space weapons, missiles and aircraft help you in the fight against poisonous mosquitoes?

This time the silence lasted for a minute. And then one of Rice’s aides said: “Well, we will bomb the mosquito nests”.

And I responded: “That’s right, you are also doing something similar now. However, the problem is that mosquitoes don’t have nests. Mosquitoes live in swamps. And you need to dry the swamp to conquer mosquitoes. You need to irrigate the land, and this is something totally different — this is not war and this is not bombing.”

And this may well be key to understanding US actions in Afghanistan, Iraq and other “hot spots”. In the 21st century, the work required is totally different: you need to eliminate excessive inequality and global monopolies, promote fair competition, display equal respect for everyone without exception, engage in international cooperation, make sure that primary education is available everywhere and establish value-based institutes. Therefore, you should not act in isolation, but instead cooperate with others and strive to achieve mutual understanding with allies and partners – with Europe and Russia. In February 2002 I failed in my attempts to communicate this idea to Americans.

FROM RUSSIA OF THE 1990S TO AFGHANISTAN

Today, almost 20 years have passed and the whole world — based on the example, first of Iraq and now Afghanistan — has seen the results of the policy of the “bombing of mosquito nests”. Over two decades the United States has still not determined the specific outcome that they wanted to achieve in these countries5 “From the very beginning, nearly two decades ago, the American military’s effort to advise and mentor Iraqi and Afghan forces was treated like a pickup game— informal, ad hoc, and absent of strategy,”, writes retired US army colonel Mike Jason. “We patched together small teams of soldiers, taught them some basic survival skills… We failed to establish the necessary infrastructure that dealt effectively with military education, training, systems, career progression, personnel, accountability—all the things that make a professional security force. We didn’t fight a 20-year war in Afghanistan; we fought 20 incoherent wars, one year at a time, without a sense of direction.” See M. Jason. What We Got Wrong in Afghanistan // The Atlantic, 12 August 2021. Available at (accessed on 31 August 2021).. This concerns both the objectives of creating an operable state and public institutes and the resolution of more specific issues related to the preparation of an efficient army and security forces.

In Afghanistan the US tried to create a national army, police, build some infrastructure, reduce mortality and increase life expectancy. They did achieve something. For example, in 2001 Afghanistan’s population of 38 million people had only 900,000 students, and not a single woman. Two decades later, on the eve of the recent power grab by the Taliban, the number of students in the country had increased to 9.5 million, of whom 39% were girls. However, it transpired that all these were clearly important, but only tactical objectives which could not be considered strategic goals.

According to US President Joe Biden, over 20 years 2,448 Americans were killed in Afghanistan, and over USD 2 trillion were spent on the country — and in the end the Taliban came back. The situation we see is the direct result of a strategically meaningless war between the USA and “mosquitoes”, backed by aircraft carriers.

It is clear that this outcome is attributable to a number of factors. One is the misperception that the value system and specifics of life6 In 1857 Friedrich Engels wrote: “The Afghans are a brave, hardy, and independent race; they follow pastoral or agricultural occupations only, eschewing trade and commerce, which they contemptuously resign to Hindus, and to other inhabitants of towns. With them, war is an excitement and relief from the monotonous occupation of industrial pursuit. The Afghans are divided into clans, over which the various chiefs exercise a sort of feudal supremacy. Their indomitable hatred of rule, and their love of individual independence, alone prevents their becoming a powerful nation; but this very irregularity and uncertainty of action makes them dangerous neighbours, liable to be blown about by the wind of caprice, or to be stirred up by political intriguers, who artfully excite their passions.” See K. Marx, F. Engels (1860). Works. Vol, 14. State Publishing House of Political Literature, Moscow, 1959. Page 78. in a specific country, its political and economic structure, can be transformed through the exercise of military and/or economic power, but without an in-depth understanding of national culture.

As a result, this entire construct based on the reforms of the 1990s collapsed, and that is how we ended up where we are now. Today, 30 years after the start of the reforms, the practices of the Soviet period are returning apace. Suffice to say that the number of political prisoners in Russia today already exceeds the number during the Brezhnev era.

Naturally, the Afghan fiasco of the Americans in this sense is more compelling and akin to a nightmare: the attempt to build a modern state through the use of force and the pumping of billions in a corrupt gravy train7 The American publicist David Vine wrote in The Guardian: “Since it invaded Afghanistan, the US has fuelled corruption in Afghanistan through CIA and military deliveries of bags of cash to Afghan power brokers and a system of bribes to ensure US troops remained fed and supplied. Absurdly, the US government has spent billions paying the Taliban not to attack convoys supplying troops sent to fight the Taliban. The vast majority of the $2.3tn the US government has spent or obligated for the war has gone not to Afghans – corrupt or otherwise – but to US military contractors (and those who bought US debt): a reported 80–90% of US outlays ended up back in the US as a “massive wealth transfer” from taxpayers to firms in the military industrial complex, which have seen their profits and stock prices skyrocket. The military industrial complex has become a system of largely legalized corruption revolving around entrenched incentives to wage endless war for financial and political gain. If we don’t end this system and the corrupting belief that war is a legitimate and useful policy tool, the United States will keep fighting endless wars.” See D. Vine “Defeat was inevitable”: our panel weighs in on the Afghanistan catastrophe // The Guardian, 19 August 2021. Available at (accessed on 31 August 2021). in the hope that artificially created elites would be able to control the situation in the country ended in fiasco. As The Financial Times wrote: “The whole point of this intervention was not to build a state, a democracy <…>, it was about counter-terrorism”8 Parkin B. Afghanistan: A history of failed foreign occupations // Financial Times, 19 August 2021. Available at (accessed on 31 August 2021)..

20 LOST YEARS

The shocking images of Kabul airport with crowds of refugees storming aircraft which had already taken off, and the Afghan army which melted into thin air an instant before the offensive of Taliban’s fighters – these represent the only tangible results of two decades of America’s “mosquito hunt”. The time lost irrevocably is still less perceptible right now, but also the key result of America’s actions in international politics.

During the 20 years that the USA fought international terror in Afghan provinces, the world changed materially, transformed from a global space, interdependent and advancing in line with the plotted direction, into an unravelling network full of holes. America’s failure in Afghanistan discussed by everyone is not the first such global experience of the USA. For example, many people recall how in 2003 the USA entered Iraq, only to try to leave in 2011, then ending up with Islamic State and compelled to return their troops. As a result, the war continued, leaving in its trace thousands of dead and millions of refugees.

Or let us take Syria. In 2012 the West talked about the use of chemical weapons by Assad’s regime against the forces of the opposition and the civilian population. Threats rained down on Damascus from Washington, with the US President Barack Obama warning about certain “red lines”9 Wordsworth D. What, exactly, is a “red line”? // The Spectator magazine, 24 October 2013. Available at/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).. However, no practical steps were taken in subsequent years other than several surgical strikes on Syrian government facilities by the USA with the support of the British and French. As a result, the civil war in Syria continues to this day (now with the pointless participation of the Russian Federation) — while suspicions regarding Assad’s use of chemical weapons remain, with half a million dead, and millions of refugees. Such an unprecedented wave of refugees since the times of World War II resulted in a systemic reboot of a global scale.

As The New York Times writes, “one of the results was the populist reaction which included “Brexit”, major successes of neofascist parties at the elections in France and Germany and perceptible assistance in Donald Trump’s presidential campaign10 Stephens B. Our “Broken Windows” World // The New York Times, 24 August 22021. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021)..

In another part of the world, the hard-line political subordination of Hong Kong to Communist China in 2018-2020 and the end of the paradigm “one country — two systems” is a landmark event for the contemporary political world order. One could add here the annexation of Crimea, the war in the Donbass, Russia’s intervention in the Syrian conflict, the military coup in Myanmar, the brutal suppression of the protests against the dictatorship in Belarus, as well as the appearance of failing states devoid of any prospects, let alone for development, but for actual survival (such as Lebanon, Haiti and a number of African countries). Indeed, the constitutional coup in summer 2020 in Russia is another major hole in the global network11 G. Yavlinsky. The Day After // Official website of Grigory Yavlinsky, 10 September 2020. Available at (accessed on 29 September 2021)..

THE WINNERS AND LOSERS

The precipitous collapse of all the Afghan state’s institutions glued together over two decades immediately after the departure of the Americans and the ostensible triumphal procession of the Taliban — this is a vivid picture of mounting global political entropy and for the time being there is no serious antidote12 G. Yavlinsky. Political Entropy // Official website of Grigory Yavlinsky. 1 December 2020. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021).. International structures are weakening, the era of America’s global dominance is ebbing, while the institutional emptiness is being filled in by post-modern trickery. And this is only the start. Biden’s Afghan failure increases significantly the likelihood that some other new authoritarian populist will win the next US Presidential elections — someone smarter and more flexible than Trump.

Neither the military, information technologies (which make it possible today to track not only, for example, the construction of missile pits in China, but also the movements of an individual over a distance of several thousand kilometres), nor artificial intelligence could prevent or even adequately forecast what happened in August 2021 in Afghanistan. Technologies have outstripped the consciousness of mankind today, but have not resolved anything of real substance13 G. Yavlinsky. Information Ochlocracy // Official website of Grigory Yavlinsky. 15 December 2020. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021)..

And the crux of the matter first and foremost is that technologies do not replace institutes. Despite the rate of development and fantastic scale of their potential, technologies remain mere tools: expecting them to somehow shed light independently on meaning and their designation is akin to believing in the spontaneous generation of children in cabbage.

Secondly, the new information technologies and their derivatives (taking into account the widespread accessibility of different gadgets and the blanket distribution of social networks) are catering successfully to destructive forces. In principle, it is far easier to wreak havoc than to counter entropy.

The Taliban of 2021, the masters of Afghanistan today, unlike the Taliban of the 1990s, is one such phenomenon — the spawning of a gap between a modern high-tech world and primaeval human nature cast aside and neglected on the periphery. This is not simply an “outbreak of archaism”, but instead something more plastic and hybrid. The new Taliban say they are ready to reach agreement with the key forces in the region and promise not to export drugs, terrorism and Islamism to neighbouring countries. It remains to be seen whether they can be trusted. However, it would appear that the Taliban have every chance of establishing a foothold in Afghanistan for a long time to come.

Who will be the beneficiary of such a development? Possibly, China. Yes, on the one hand, the Chinese authorities might have to deal with a number of problems related to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region as a result of recent events in Afghanistan. On the other hand, given that the Taliban 2.0 version is no stranger to Bolshevik pragmatism (retaining power takes precedence over patronage of any fundamentalists and the export of the Jihad), the Chinese may offer poor neighbours something similar to economic cooperation and investments. Consequently, after the departure of the USA from Afghanistan, China could occupy the new void through something similar to China’s Belt and Road Initiative14 “The Belt and Road Initiative is a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013 to invest in nearly 70 countries and international organizations”. Wikipedia. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021). Establishing relations with China is underpinned by the significant or even overriding influence of Pakistan on the Taliban, while Pakistan and China have one common foe — India.

Today the people of Afghanistan are confronted by a fluid and uncertain situation and are in grave danger. While the flight from Kabul is a major strategic failure for the USA, it is testimony to the rest of us that the world has changed and an important indicator of the factors which will determine the immediate future.

A NEW ERA OF TURMOIL AND DISORDER

The departure from Afghanistan and Biden’s position articulated in connection with this decision15 Remarks by President Biden on Afghanistan. The White House official site, 16 August 2021. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021) showed that the USA finds it easy to cast aside moral principles and ethical considerations. It would now seem that there is no place for values in America’s foreign policy. Incidentally, this is indicative of the new concept of “real politics”. Biden is following in the footsteps of his predecessors Obama and Trump, signalling that America is sick and tired of foreign military conflicts, in particular in Central Asia and the Middle East.

This means at the very least that it is highly likely the USA will over the next ten years use its armed forces only in the event of a direct threat and de facto will not participate in maintaining so-called international security. The borders determining US national interests will be stringently delineated and narrowed significantly.

The Financial Times asks: “How sure can NATO allies be that, if it comes to the crunch with Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the White House will judge the defence of Europe’s borders a vital US interest?”16 Stephens P. Europe had better face facts about the Biden doctrine // Financial Times, 19 August 2021. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021).

A number of people in the USA — possibly, even fairly — were perplexed as to why over two trillion dollars had been spent in Afghanistan and on what. At the same time, however, how does one calculate the cost to everyone, including America, if the USA forfeits its status as “global policeman” after the evacuation from Kabul? For that matter, it is unclear how certain regions in the world will look now that the United States has decided to step back from the rest of the world.

The New York Times notes: “We have turned the corner into a world of unlit streets, more hospitable to predators than it is to prey. In this world, the temptation can only grow stronger for Putin to break the back of NATO by picking off a vulnerable member like Latvia. Ditto for China seizing Taiwan.” 17 Stephens B. Our “Broken Windows” World // The New York Times, 24 August 2021. Available at (accessed on1 September 2021).

Consequently, we need to realise that in the future global autocrats, dictators and aggressors of differing hues will be free of the restraining influence of the USA. It is time to understand and acknowledge that the old order is rapidly receding into the past, and that relations both with allies and enemies will become far tougher in the era of political entropy and digital technologies. And the main conclusion from this new configuration is that from now on we can only count on ourselves.

It goes without saying that America and the world as whole have a different experience. This is also the decisive influence of the US on the post-war recovery of stars of the global economy — Japan and Western Europe — and the protection and key role it played in the emergence of a successful South Korea.

Why then did it transpire in the 1950s-1960s, and since the mid-1970s that the United States gradually, with ups and downs, lost the role of a power bringing to the world, freedom, democracy and an effective economy? Possibly the answer here is that the period of success was a direct result of the institutionalisation of the values acquired through pain and struggle in World War II: the priority of human rights, respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, the supremacy of law18 G. Yavlinsky. What Should Be Done? Institutionalisation of Values// Official website of Grigory Yavlinsky, 30 December 2020. Available at (accessed on 1 September 2021). In other words, the factors underpinning the foundation of the European Union.

Naturally, I am not saying that we need to turn back to some period in history. The key issue here is that it is becoming clear that there is an acute need for a strategic transformation in the consciousness of global elites (for the time being, they can still be called “global elites”). However, to do this, we need to find our place in modern history, understand the concept of time and determine real, and not contrived, development goals for the next decades. In other words — acquire the future.